Table Of Contents

Financing Acquisitions Meaning

Financing an acquisition is the process in which a company that plans to buy another company tries to get funding via debt, equity, preferred equity, or one of the many alternative methods available. It is a complex task and requires sound planning. What makes it complex is that, unlike other purchases, the financing structure of M & M&A can have plenty of permutations and combinations.

Table of contents

- Financing Acquisitions Meaning

- Financing an acquisition refers to the process of a company purchasing another company and attempting to secure funding through various means, including debt, equity, preferred equity, or other alternative methods. Unlike traditional purchases, the financing structure for M&A transactions can involve various combinations and changes.

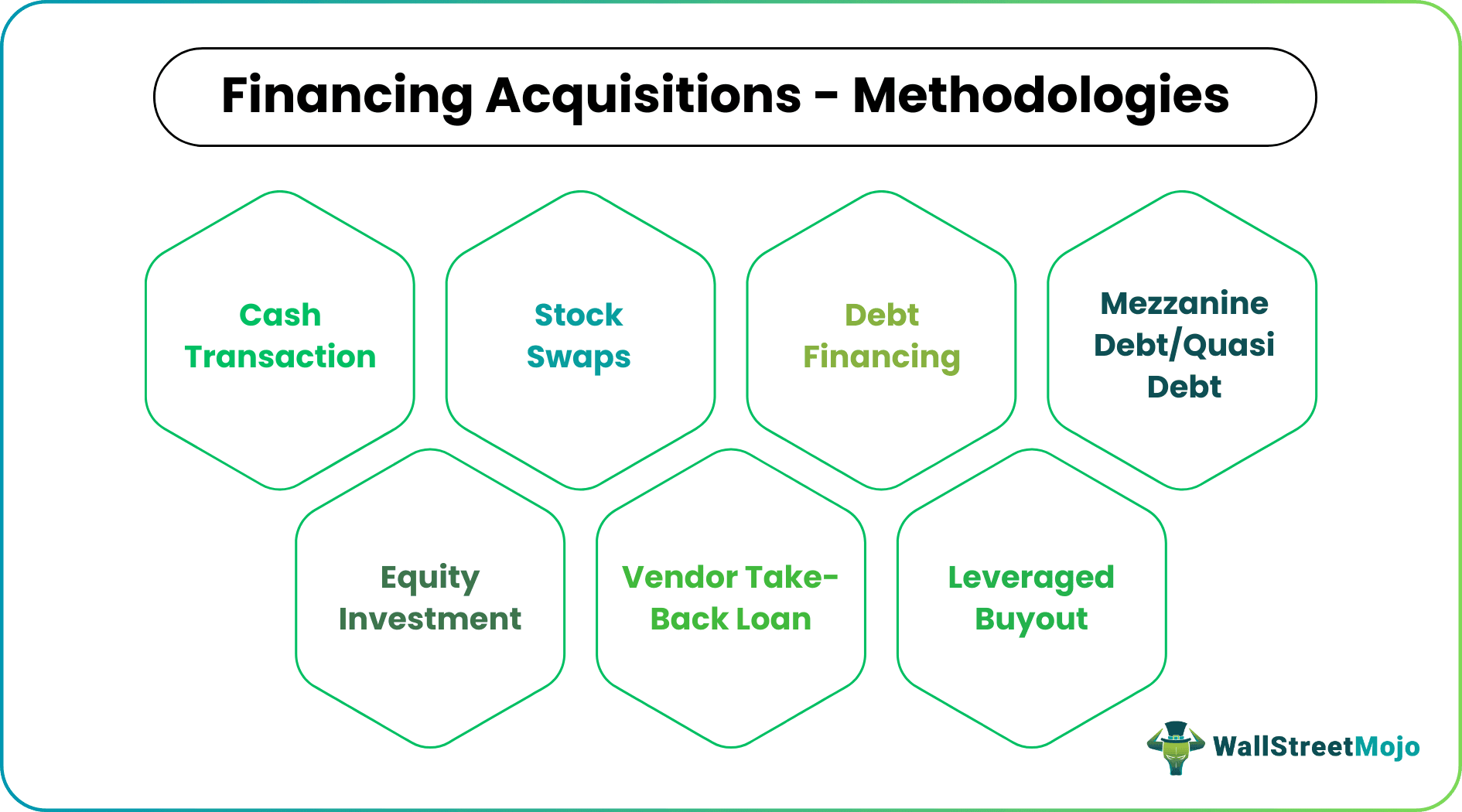

- Cash transactions, stock swaps, debt financing, mezzanine or quasi-debt, equity investment, vendor take-back loans (VTBs), seller financing, and leveraged buyouts are among the different debt and equity methodologies used to finance business acquisitions.

- In significant acquisitions, companies may use a combination of two or more financing approaches to secure the necessary funds for the transaction.

How to Finance a Business Acquisition?

There are many ways in which you can finance the business acquisition. Popular methodologies are listed below.

- #1 - Cash transaction

- #2 - Stock Swaps

- #3 - Debt financing

- #4 - Mezzanine Debt/ Quasi Debt

- #5 - Equity investment

- #6 - Vendor Take-Back Loan (VTB) or seller's financing

- #7 - Leveraged Buyout: A unique mix of debt and equity

Please note in large acquisitions, financing business acquisition can be a combination of two or more methods.

#1 - Cash transaction

In an all-cash deal, the transaction is simple. Shares are exchanged for cash. In the case of an all-cash deal, the equity portion of the parent company's balance sheet is unchanged. This transaction mostly occurs when the acquiring company is much larger than the target company and has substantial cash reserves.

In the late 80s, most of the large M&A deals were paid entirely in cash. But after a decade, the trend reversed. More than 50% of all large deals' value was paid for entirely in stock, while cash transactions were cut to only 15% to 17%. Stock accounted for less than 2%.

This shift was quite a tectonic one as it altered the roles of the parties concerned. The two parties' roles were clearly defined in a cash deal, and the barter of money for shares depicted a simple transfer of ownership. The main tenet of all-cash transactions was that once the acquirer pays cash to the seller, it automatically acquires all company risks. However, in a share exchange, the risks are shared in the proportion of ownership in the new and combined entity. Though the proportion of cash transactions has reduced drastically, it hasn’t become redundant altogether. For instance, a very recent announcement by Google to cloud software company Apigee in a deal valued at about $625 million. It is an all-cash deal, with $17.40 paid for each share.

source: reuters.com

In another instance, Bayer has planned to acquire US seeds firm Monsanto in a $128 a share deal, which is being touted as the largest cash deal in history.

#2 - Stock Swaps

One very common method for companies whose stock is publicly traded is to exchange the acquirer's stock for Target Company. If the owner of Target Company is involved in the active management of operations and the company's success depends on their proficiency, then the share swap is a valuable tool.

For private companies, it is a sensible option when the owner of Target would like to retain some stake in the combined entity.

Appropriate stock valuation is of utmost importance in a stock swap for private companies. Experienced merchant bankers follow certain methodologies to value the stocks, such as:

- 1) Comparable Company Analysis

- 2) Comparable Transaction Valuation Analysis

- 3) DCF Valuation

source: koreaherald.com

#3 - Debt Financing

One of the most preferred ways of financing acquisitions is debt financing. Paying out of cash isn’t the forte of many companies, or it is something that their balance sheets don’t permit. It is also said that debt is the cheapest method of financing an M & M&A bid and has many forms.

Usually, while disbursing funds for the acquisition, the bank scrutinizes the projected cash flow of the target company, its liabilities, and its profit margins. Thus, as a prerequisite, the companies' financial health, Target, and the acquirer are thoroughly analyzed.

Another method of financing is Asset-backed financing, where banks lend finance based on the collaterals of the target company on offer. These collaterals refer to fixed assets, inventory, intellectual property, and receivables.

Debt is one of the most sought-after forms of financing acquisitions due to the lower cost of capital than equity. Plus, it also offers tax advantages. These debts are mostly Senior debt or Revolver debt, come with a low-interest rate, and the quantum is more regulated. The rate of return is typically a 4%-8% fixed/ floating coupon. There is also subordinated debt, where lenders are aggressive in the amount of loan disbursed, but they charge a higher interest rate. Sometimes there is also an equity component involved. The coupon rate for these is typically 8% to 12 % fixed/floating.

source: streetinsider.com

#4 - Mezzanine Debt/ Quasi Debt

Mezzanine financing is an amalgamated form of capital with debt and equity characteristics. It is similar to subordinate debt in nature but comes with conversion to equity. Target companies with a strong balance sheet and consistent profitability are best suited for mezzanine financing. These companies do not have a strong asset base but boast consistent cash flows. Mezzanine debt or quasi debt carries a fixed coupon of 12% to 15%. It is slightly higher than the subordinate debt.

The appeal of Mezzanine financing lies in its flexibility. It is a long-term capital that can spur corporate growth and value creation.

#5 - Equity investment

We know that the most expensive form of capital is equity and the same goes for the case of acquisition financing. Equity comes at a premium because it carries maximum risk. The riskiness arises out of having no claim to the company's assets. The high cost is the risk premium.

Acquirers who target companies operating in volatile industries and have unstable free cash flows usually opt for more equity financing. Also, this form of financing allows more flexibility because there is no commitment to periodic scheduled payments.

One of the crucial features of financing acquisitions with equity is relinquishing ownership. The equity investors can be corporations, venture capitalists, private equity, etc. These investors assume some ownership or representation in the Board of Directors.

source: bizjournals.com

#6 - Vendor Take-Back Loan (VTB) or seller's financing

Not all sources of financing are external. Sometimes the acquirer seeks financing from the target firms as well. The buyer typically resorts to this when he faces difficulty obtaining outside capital. Some of the ways of seller financing are notes, earn-outs, delayed payments, consulting agreements, etc. One of these methods is a seller note, where the seller loans money to the buyer to finance acquisitions, wherein the latter pays a certain portion of the transaction later.

Read more about Vendor take-back loan here.

#7 - Leveraged Buyout: A unique mix of debt and equity

We have understood the features of debt and equity investments, but there are certainly other forms of structuring the deal. One of the most popular forms of M&A is Leveraged Buyout. Technically defined, LBO is a purchase of a public/ private company or the assets of a company financed by a mix of debt and equity.

Leveraged buyouts are quite similar to usual M&A deals; however, in the latter, there is an assumption that the buyer offloads the target in the future. More or less, this is another form of a hostile takeover. It is a way of bringing inefficient organizations back on track and re-calibrate the position of management and stakeholders.

The debt-equity ratio is more than 1.0x in these situations. The debt component is 50-80% in these cases. Both the Acquirer and Target Company assets are treated as secured collaterals in this type of business deal.

The companies involved in these transactions are typically mature and generate consistent operating cash flows. According to Jennifer Lindsey in her book , the best fit for a successful LBO will be in the growth stage of the industry life cycle, have a formidable asset base as collateral for huge loans, and feature crème-de-la-crème in management.

Having a strong asset base doesn’t mean that cash flows can take a back seat. The target company must have strong and consistent cash flow with minimal capital requirements. The low capital requirement stems from the condition that the resultant debt must be repaid quickly.

Other factors accentuating the prospects for a successful LBO are a dominant market position and a robust customer base. So it’s not just about finances, you see!

Now that we have certain learning about LBOs let us figure out a little about their background. It will help us understand how it came into being and how relevant it is today.

LBOs soared during the late 1980s amid the junk-bond-finance frenzy. The high-yield bond market financed most of these buyouts, and the debt was mostly speculative. The junk bond market collapsed by the end of 1980, excessive speculation cooled off, and the LBOs lost steam. What followed was a tighter regulatory mechanism and stringent capital requirement rules, due to which commercial banks lost interest in financing the deals.

source: econintersect.com

The volume of LBO deals resurged in the mid-2000s due to the growing participation of private equity firms that secured funds from institutional investors. High-yield junk bond financing gave way to syndicated leveraged loans as the main source of financing.

The core idea behind LBOs is to compel organizations to produce a steady stream of free cash flows to finance the debt taken for their acquisition. It mainly prevents the siphoning off of the cash flows to other unprofitable ventures.

The table below illustrates that over the last three decades, the buyout targets generated greater free cash flow and incurred lower capital expenditure as compared than their non-LBO counterparts.

source: econintersect.com

Pros and cons are two sides of the same coin, and both co-exist. So LBOs also come with their share of drawbacks. The heavy debt burden heightens the default risks for buyout targets and becomes more exposed to downturns in the economic cycle.

KKR bought TXU Corp. for $45 billion in 2007. It was touted as one of the largest LBOs in history, but by 2013 the company filed for bankruptcy protection. The latter was burdened with more than $40 billion for debt, and unfavorable industry conditions made things worse for the US utility sector. One event led to the other, and eventually and quite, unfortunately, of course, TXU Corp. filed for bankruptcy.

But does that mean LBOs have been black-listed by US corporations? "No." The Dell-EMC deal that closed in September 2016 indicates that Leveraged buyouts are back. The deal is worth about $60 billion, with two-thirds of it financed by debt. Will the newly formed entity produce enough cash flows to service the massive debt pile and wade its way through the deal's complexities is something to be seen.

source: ft.com

Flexibility & Suitability is the name of the game

Financing for acquisitions can be procured in various forms, but what matters most is how optimal it is and how well-aligned it is with the nature and larger goals of the deal. Designing the financing structure according to the suitability of the situation matters most. Also, the capital structure should be flexible enough to be changed according to the situation.

While debt and equity share the largest pie, other forms also find their existence due to the uniqueness of each deal. Debt is undoubtedly cheaper than equity, but the interest requirements can curtail a company's flexibility. Large amounts of debt are more suitable for mature companies with stable cash flows and aren’t required for any substantial capital expenditure. Companies that are eyeing rapid growth require a massive quantum of capital for growth, and competing in volatile markets are more appropriate candidates for equity capital.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Financing acquisitions with earnouts is a common method of structuring a deal where a portion of the purchase price is contingent upon the acquired company achieving future financial or operational goals. This type of financing can help mitigate the risk for the acquiring company by aligning the interests of both parties. It is often used when there is uncertainty about the future performance of the acquired company.

Yes, financing acquisitions can vary between countries due to differences in legal and regulatory environments, financing sources, and cultural norms. For example, in some countries, debt financing may be more accessible and less expensive than equity financing, while in others, equity financing may be the preferred option.

Macroeconomic conditions such as interest rates, inflation, and GDP growth can significantly impact the availability and cost of financing for acquisitions. For example, high-interest rates can make debt financing more expensive, while low-interest rates can make it easier to access debt financing. Similarly, inflation and GDP growth can affect investor sentiment and the cost of equity financing.