Table Of Contents

Dutch Auction Meaning

Dutch auction in finance is the process of finding the optimum price at which the government agency or company wants to sell its assets or securities. The seller establishes an opening price that steadily decreases until a bid (quantity and cost) is placed. Unlike typical initial public offerings (IPOs), the Dutch auction strategy work without underwriters or investment banks.

The auctioneer reduces the asking price until collecting all bids to sell the total shares in this method, also known as descending or uniform price auction. Following the submission of all bids, the price with the most bidders becomes the new offering price for the entire offering. After the price reaches an optimal level, the remaining bidders must purchase securities at that rate.

Key Takeaways

- In finance, a Dutch auction is a process of determining the best price for a government agency or firm to sell its assets or securities. Companies frequently utilize this strategy to go public but do not want underwriters to set the rules.

- The seller chooses the number of shares to be sold and the opening price, while the bidders determine the selling price.

- The auctioneer begins at the highest offering price and works their way down until all bids (quantity and cost) have been submitted and all shares have been sold.

- Unlike traditional IPOs, this technique does not necessitate underwriters or investment banks.

How Does Dutch Auction Work?

The Dutch auction method allows public and private entities to sell their assets or securities on their terms, and it is common in initial public offerings (IPOs). It is often used by a firm that wants to go public but does not wish underwriters to define its rules. It enables companies to make their IPOs accessible to individual investors, allowing them to keep an eye on the price fall and submit bids at a reasonable price.

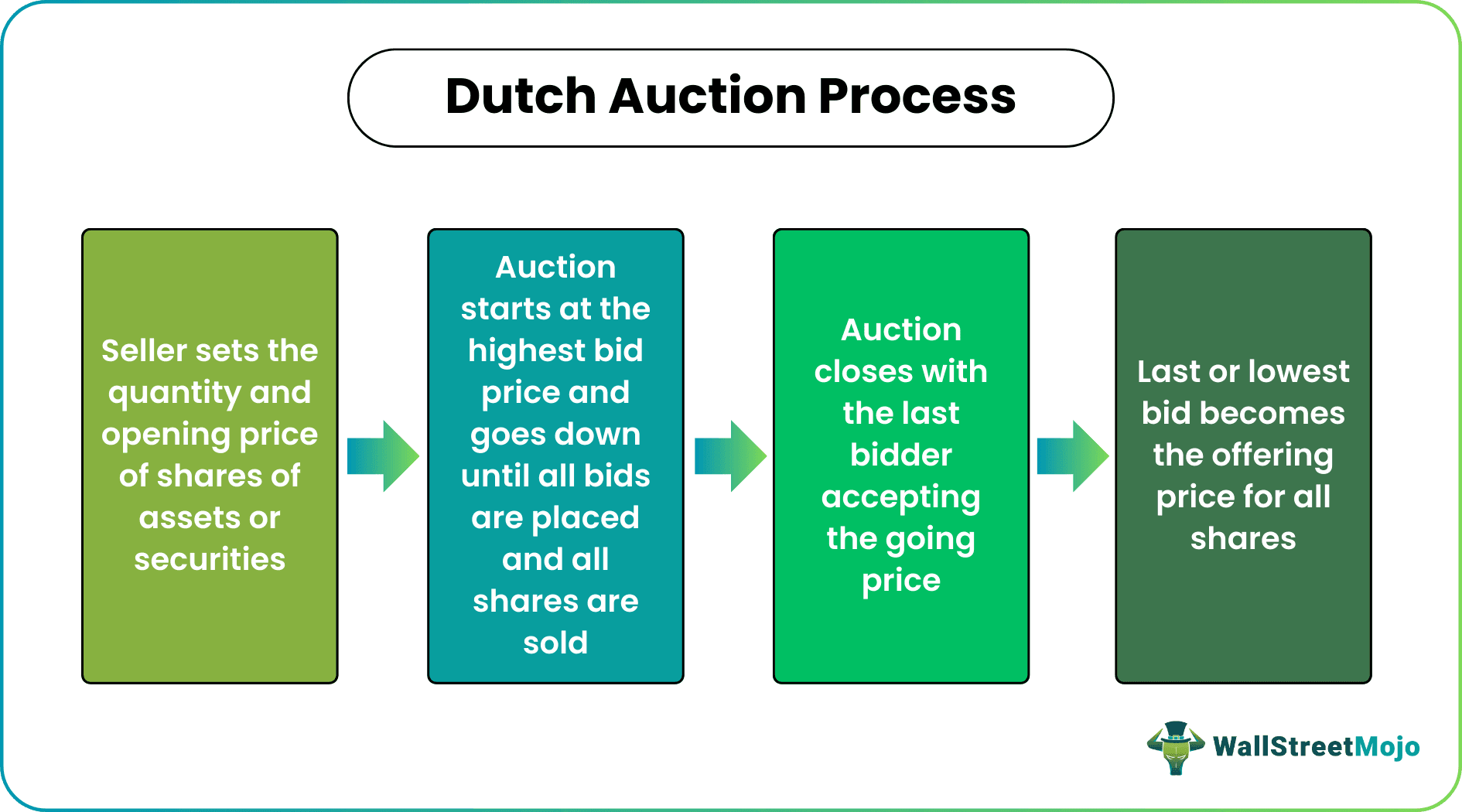

The seller determines the quantity and opening price of shares to be sold, while the bidders determine the selling price. First, investors submit bids for their number and specified price of shares they want to buy and pay. After that, the auction starts at the highest bid price and goes down until all bids (quantity and cost) are placed, and all shares are sold. Finally, the auction closes with the last bidder accepting the going price.

The last or lowest bid becomes the offering price for all shares, which all investors must pay. As a result, even buyers who bid higher prices for the shares will be able to purchase the appropriate number of shares for lower per-unit rates.

For example, if investor A places a bid for 10,000 shares at $65 each and investor B places a bid for 20,000 shares at $50 each, the firm will choose the latter as the profit would be more by selling more shares at a lower unit price.

The Dutch auction allows individual investors to find the best traditional offerings. As a result, they benefit more and more by buying shares at lower prices and selling them at higher bid prices. Likewise, the U.S. Treasury sells its Treasury Bills (T-Bills), notes (T-notes), and bonds (T-bonds) using this auction.

Many traders use Saxo Bank International to research and invest in stocks across different markets. Its features like SAXO Stocks offer access to a wide range of global equities for investors.

Dutch Auction vs Traditional IPO

In the traditional IPO, an investment bank or underwriter determines the price of shares. These intermediaries define multiple parameters for evaluations and consult potential investors to decide on the IPO pricing. In contrast, the Dutch auction helps the entity find the right price in an IPO auction to maintain the supply and demand balance. That is why it is a more efficient way of going public through traditional IPOs rather than choosing blank check companies or Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs).

Examples

Let us consider the following Dutch auction examples to get a better insight into the concept:

Example #1

A public entity wants to sell 1 million shares to investors, and hence, it opens the bids for them. Here are the bids placed:

- Investor A for 100,000 at $65 each

- Investor B for 200,000 at $60 each

- Investor C for 400,000 at $50 each

- Investor D for 100,000 at $70 each

- Investor E for 200,000 at $60 each

The entity chooses the lowest bid with the highest number of shares and finalizes selling the shares at $50 each. As a result, the shares become available to all investors at the lowest rate even though they have placed higher bids.

Example #2

In 2004, Google sold approximately 20 million shares with at least five bids. The aim was to enjoy short-term gains from trading securities. In addition, it allowed its loyal customers some ownership as part of its reward program. Another reason behind the Google Dutch auction was to build a strong shareholder base.

Pros and Cons of Dutch Auction

Though Dutch auction has many advantages, it has a few drawbacks too. So let us take a quick look at the pros and cons of the process:

Pros

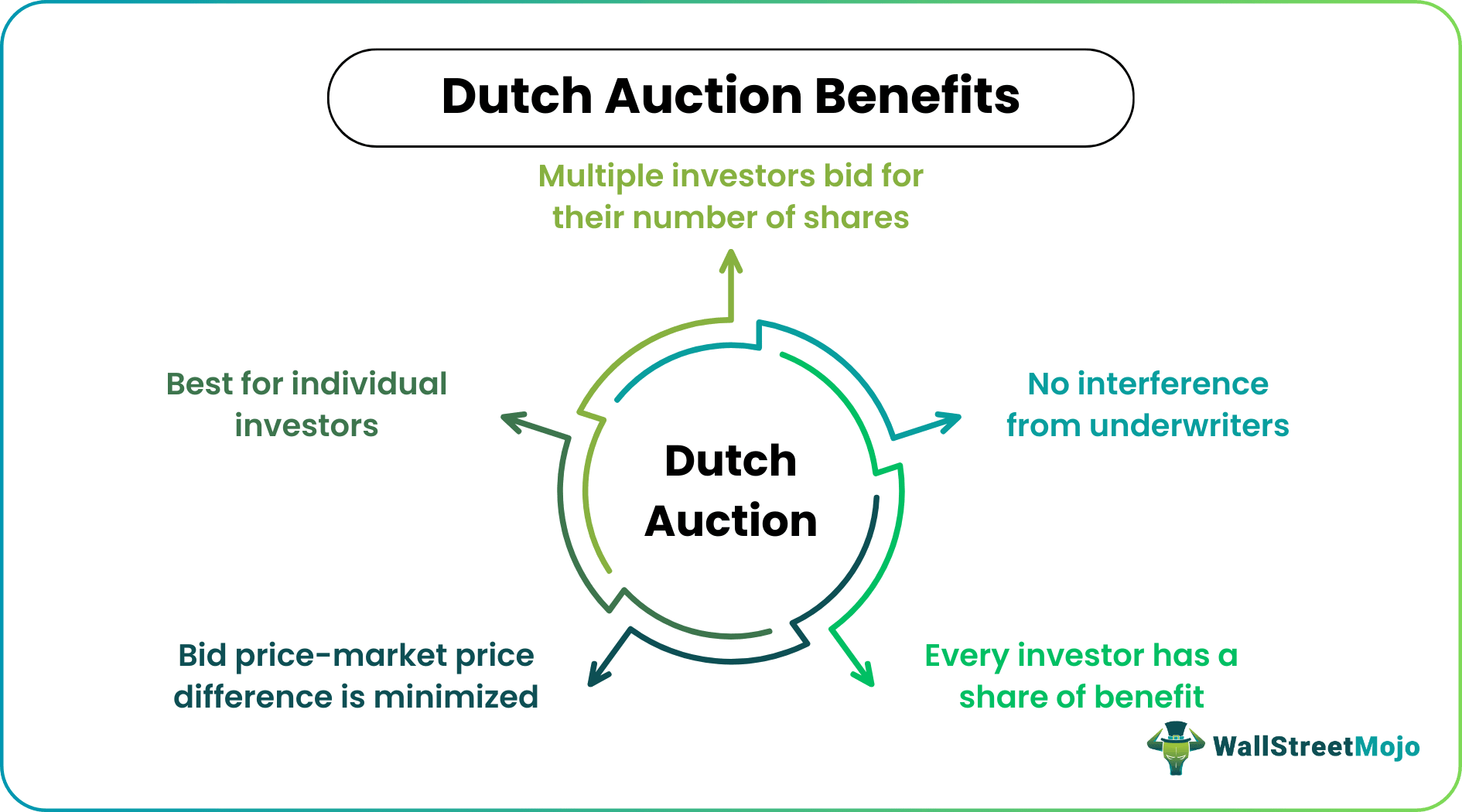

- Anyone from individual to investors can place bids, thus democratizing public offerings.

- Multiple investors bid for their number of shares, and each investor remains unknown of the other’s bid. They all place a bid that is favorable to them. As a result, all investors benefit when the auctioneer or seller selects the lowest bid.

- Public bidding increases price transparency.

- It offers firms a chance to go public without taking the help of underwriters or investment banks, thus reducing transaction costs.

- It reduces the spread between the bid (offering) and actual market (opening/listing) prices for assets or securities.

Cons

- As the bid is open to all types of investors, the estimated offering price might differ from the companies' prospects from whom investors have decided to purchase shares.

- Bidders may find they have overbid due to the higher bid pricing. As a result, they attempt to sell their stake to liquidate their holdings, causing stock prices to plummet.

- Auction-based pricing gives investors less control.

- Lack of information about the seller and the auction process may result in inappropriate share pricing and increased risks.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links. If you sign up through these links, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

The Dutch auction allows public and private companies to sell assets and securities on their terms. The auction begins with the highest offering price once all bids (quantity and cost) have been submitted that continue to decrease until all shares have been sold. When the price reaches an optimal level, the auction ends. Finally, the lowest bid becomes the offering price for all shares, which all investors must pay.

A company chooses a Dutch auction when it wants to go public without the involvement of underwriters. It allows them to keep their IPOs accessible to small investors, allowing them to keep an eye on the price decrease and submit bids at a reasonable price.

The investors place their bids for the number of shares they wish to buy. The lowest bid above the reserve price becomes the winning bid. It becomes the final price for the securities that all other investors must pay per share.