Table Of Contents

What Are Asset-Backed Securities?

Post the global financial crisis of 2008, there was a huge buzz about some sophisticated financial securities known as CDOs, CMBS, & RMBS, and how they played a big role in the build-up of the crisis. These securities are known as Asset-backed Securities (ABS), an umbrella term used to refer to a kind of security that derives its value from a pool of assets, which could be a bond, home loan, car loan, or even credit card payments.

ABS allows investors to gain exposure to a diversified pool of underlying assets, reducing risk. They also enhance liquidity in financial markets by creating tradable securities backed by various types of assets. However, asset backed securities fund structures can be complex, making it challenging for investors to understand their risks fully.

Key Takeaways

- Asset-backed securities (ABS) are financial instruments representing claims on underlying assets like mortgages, auto loans, or credit card receivables.

- The creation of ABS involves securitization, a process where individual loans or assets are pooled and transferred to a special purpose vehicle (SPV).

- ABS manages risk and enhances credit quality through over-collateralization, reserves, and third-party credit enhancements.

Asset-Backed Securities Explained

The creation of ABS provides an opportunity for large institutional investors to invest in higher-yielding asset classes without taking much additional risk, and at the same time, helps lenders in raising capital without accessing primary markets. It also allows the banks to remove the loans from their books as the credit risk for the loans gets transferred to the investors.

The process of pooling of financial assets so that they could be sold to the investors later is called Securitization(we’ll take a deeper look into the process in the later section using examples), done usually by Investment Banks. In the process, the lender sells its portfolio of loans to an Investment Bank, which then repackages these loans as a Mortgage-Backed Security (MBS) and then sells it off to other investors after keeping some commission for themselves.

Types

Let us understand the different types of ABS in the asset backed securities market through the discussion below.

- RMBS (Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities),

- CMBS (Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities) and

- CDOs (Collateralized Debt Obligations).

There are certain overlaps in these instruments as the basic principle of Securitization broadly remains the same while the underlying asset might differ.

Let’s take a look at the different types of Asset-backed Securities:

RMBS (Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities)

- RMBS is a type of mortgage-backed debt securities where the cash flows are derived from residential mortgages.

- These securities can contain all of one type of mortgage or a mix of different types such as prime (High quality and high creditworthy loans) and subprime (Loans with lower credit ratings and higher interest rates) mortgages.

- Unlike commercial mortgages, apart from the risk of default on the loans, residential mortgages also pose a risk of prepayment (As prepayment charges on residential mortgages are very low or nil) of the loan from the lender’s perspective, which impacts the expected future cash flows.

- Since the RMBS consists of a large number of small mortgage home loans that are backed by the houses as collateral, the default risk associated with them is quite low (Chances of a large number of borrowers defaulting on their repayments at the same time is very low).

- This helps them in getting a higher credit rating as compared to the underlying assets.

- Institutional investors, including insurance companies, have historically been important investors in RMBS, due in part to the long-term cash flows they provide.

- RMBS could be issued by federally backed agencies like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as well as private institutions like banks.

Structure of RMBS

Let's have a look at the structure of RMBS and how they are created:

- Consider a bank that gives out home mortgages and has lent out $1bn worth of total loans distributed among thousands of borrowers. The bank will receive repayments from these loans after 5-20 years, depending on the tenure of the loans outstanding.

- Now to lend out more loans, the bank will need more capital, which can be raised in several ways, including secured/unsecured bond issuance or equity issuance. Another way the bank can raise capital is by selling the loan portfolio or a part of it to a securitization agency like the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA), commonly known as Fannie Mae. Due to their stringent requirements, the loans bought by Fannie Mae need to conform to high standards(Unlike the non-agency RMBS issued by private institutions, which are very similar to CDOs).

- Now Fannie Mae pools these loans based on their tenures and repackages them as RMBS. Since these RMBS are guaranteed by Fannie Mae (Which is a Government-backed agency), they are given a high credit rating of AAA and AA. Because of high ratings of these securities, risk-averse investors like large Insurance firms and Pension funds are the major investors in such securities.

We’ll look at an example to get a better understanding of RMBS:

RMBS (Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities) Example

Let’s say a bank has 1000 outstanding residential loans worth $1m, each with a maturity of 10 years. Thus the total loan portfolio of banks is $1bn. For ease of understanding, we’ll assume the rate of interest on all these loans is the same at 10%, and the cash flow is similar to a bond wherein the borrower makes annual interest payments every year and pays the principal amount at the end.

- Fannie Mae purchases the loans from the bank for $1bn(the bank might charge some fees in addition).

- annual cash flow from loans would be 10% * 1bn = $100mn

- cashflow in 10th year = $1.1bn

- assuming Fannie Mae sells 1000 units of RMBS to investors worth $1mn each

- After incorporating the fees of 2% charged by Fannie Mae for taking the credit risk, the yield for investors would be 8%.

Though the yield might not seem to be very high, considering the high credit rating and the yields provided by investment securities with similar credit ratings being 1-2% lower. It makes them a very attractive investment option for low-risk investors like Insurance firms and pension funds.

The risk associated with RMBS comes into play when the borrowers start defaulting on their mortgages. A small number of defaults, say 10 out of 1000, will not make much of a difference from the investor’s point of view, but when a large number of borrowers default at the same time, it becomes an issue for investors as the yield generated gets significantly impacted.

CMBS (Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities)

- Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities are a type of mortgage-backed security that is backed by commercial real estate loans rather than residential real estate.

- These commercial real estate loans are given for income-generating real estate, which could be loaned for properties such as apartment complexes, factories, hotels, warehouses, office buildings, and shopping malls.

- Similar to RMBS, CMBS are created when a lender takes a group of loans outstanding on its books, bundles them together, and then sells them in securitized form as mortgage-backed security similar to bonds in terms of its cash flows.

- CMBS are usually more complex securities owing to the nature of underlying property loan assets. Unlike residential mortgages, where the prepayment risk is usually quite high, in case of commercial mortgages, this isn't the case. This is due to the fact that commercial mortgages usually contain a lockout provision and significant prepayment penalties, thus essentially making them fixed-term loans.

- CMBS issues are usually structured into multiple tranches based on the riskiness of the cashflows.

- The tranches are created in such a way that senior tranches will bear the lesser risk as they hold the first right to the cash flows (interest payments) generated; thus are given higher credit ratings and provide lower yields.

- While the junior tranche bearing higher risks generates their cash flows from interest and principal payments; thus are given lower credit ratings and provide higher yields.

Structure of CMBS

Let’s have a look at the structure of CMBS and how they are created:

- Consider a bank that gives out commercial mortgages for properties such as apartment complexes, factories, hotels, warehouses, office buildings, and shopping malls. And has lent out a certain sum of money for various durations across a diversified set of borrowers for commercial purposes.

- Now the bank will sell its commercial mortgage loan portfolio to a securitization agency like Fannie Mae (as we saw with RMBS), which then bundles these loans into a pool and then creates a series of bonds out of these termed various tranches.

- These tranches are created based on the quality of loans and the risk associated with them. The senior tranches will have the highest payment priority, would be backed by high-quality shorter duration (As the risk associated is lower) loans, and will have lower yields. While the junior tranches will have lower payment priority, they would be backed by longer-term loans and will have higher yields.

- These tranches are then assessed by rating agencies and assigned ratings. The senior tranches will have higher credit ratings falling within the Investment grade (rating above BBB-) category while the junior tranches with lower ratings will fall within the High yield (BB+ and below) category.

- This gives investors the flexibility to choose the type of CMBS security based on their risk profile. Large institutional investors with a low-risk profile would prefer to invest in senior-most tranches (rated AA & AAA), while risky investors like hedge funds and trading firms might prefer lower-rated bonds due to higher returns.

CDOs (Collateralized Debt Obligations)

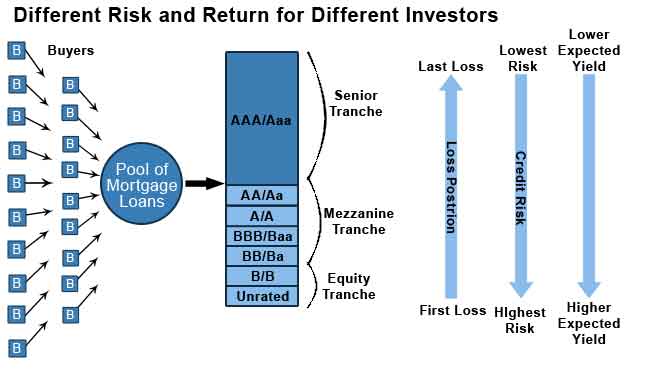

- Collateralized Debt Obligations are a form of structured Asset-Backed Security wherein the individual fixed-income assets (could range from residential mortgage and corporate debt to credit card payments) are pooled and repackaged into discrete tranches (as we saw with CMBS) based on the riskiness of the underlying fixed-income assets and are then sold into the secondary market.

- The risk profile of different tranches carved out of the same set of fixed income assets could vary substantially.

- The tranches are assigned credit ratings by rating agencies based on the risk they carry.

- The senior tranche is assigned the highest rating of AAA as they carry the lowest risk though with lower yields. The middle tranches with a moderate risk-rated between AA to BB are known as a Mezzanine tranche.

- The bottom tranche, which has the lowest rating (in financial parlance, Junk rating) or is unrated, is termed as Equity tranche, and they carry the highest risk as well as higher expected yield.

- In case the loans in the pool start defaulting, the equity tranche will be the first to take losses while the senior tranche might remain unaffected.

- An interesting aspect of CDOs is that they can be created out of any fixed-income asset, which could even be other CDOs.

- For example, it is possible to create a new CDO by pooling sub-prime mortgages or equity tranches of numerous other CDOs (which are basically junk-rated) and then creating a senior tranche from this CDO, which will have a substantially higher rating compared to the underlying asset (Actual process is a lot more complicated but the basic idea remains same).

- This was a common practice during the pre-financial crisis years and had a major role in the creation of the asset bubble.

- The subprime mortgages, in a way, became fuel for the creation of such securities and were being disbursed to anyone and everyone without requisite due diligence.

CDO Example

Let’s look at an example to get a better understanding of CDOs:

Consider a bank that has 1000 outstanding loans (including residential and commercial) worth $1m, each with a maturity of 10 years. Thus the total loan portfolio of a bank is $1bn. For ease of understanding, we’ll assume the rate of interest on all these loans is the same at 10%, and the cash flow is similar to a bond wherein the borrower makes annual interest payments every year and pays the principal amount at the end.

- An investment bank purchases the loans from the bank for $1bn(the bank might charge some fees in addition).

- annual cash flow from loans would be 10% x 1bn = $100mn

- cashflow in 10th year = $1.1bn

- Now, assuming the investment bank pools these loan assets and repackages them into three tranches: 300,000 units of the senior tranche, 400,000 units of the mezzanine tranche, and 300,000 units of equity tranche worth $1000 each.

Also, for the ease of calculation for the example, we’ll assume that investment bank will include their commission fees in the cost

- Since the risk for the Senior tranche is lowest, let’s say the coupon arrived at for them is $70 per unit. Resulting in a yield of 7% for them

- For the Mezzanine tranche, considering the coupon amount arrived at is $90 per unit, giving them a 9% yield

- Now for the Equity tranche, the coupon amount will be the remaining sum left after paying off Senior and Mezzanine

- So, total pay-off to Senior tranche = $70 x 300,000 = $21mn

- total pay-off to Mezzanine tranche = $90 x 400,000 = $36mn

- Thus, the remaining amount for Equity tranche will be $100mn – ($21mn + $36mn) = $43mn

- Per unit coupon pay-off comes out to be = $43mn/300k = $143.3

- Thus giving the equity tranche holders a yield of 14.3%

That looks very attractive compared to other tranches! But remember, here we’ve considered that all the borrowers paid their payments and there was 0% default on payments

- Now let’s consider the case wherein due to market crash or economic slowdown, thousands of people lost their jobs and now aren’t able to pay the interest payment on their loans.

- Let’s say this results in 15% of borrowers default on their interest payments.

- Thus, instead of total cash flow being $100mn, it comes out to be $85mn

- The whole loss of $15mn will be taken by Equity tranche, leaving them with $28mn. This will result in a per-unit coupon of $93.3 and a yield of 9.3%, almost the same as a mezzanine tranche.

This highlights the risk attached to the lower tranches. In case the default was 40%, the entire coupon payment of the Equity tranche would’ve been wiped out.

Risks

The risks in the asset backed securities fund can be split into four main types- credit risk, prepayment risk, market risk, and structural risk. Let us understand each of them in detail through the explanation below.

Credit Risk

- Asset-backed securities (ABS) are subject to credit risk, which arises from the possibility of default by the underlying assets, such as mortgages, auto loans, or credit card debt.

- If borrowers default on their payments, the cash flows supporting the ABS may be impaired, leading to losses for investors.

Prepayment Risk

- ABS backed by assets with prepayment options, such as mortgages or auto loans, face prepayment risk.

- Rapid prepayments can reduce the expected cash flows and returns on the ABS, negatively impacting investor returns.

Market Risk

- ABS is also exposed to market risk, including interest rate risk and liquidity risk.

- Changes in interest rates or market conditions can affect the value of ABS, making them more or less attractive to investors.

Structural Risk

- The structure of ABS, including the priority of payment to different tranches, can affect the risk profile.

- Subordination of junior tranches to senior tranches may increase the risk of loss for investors in the junior tranches in the event of defaults.